I know one thing: that I know nothing.

Socrates

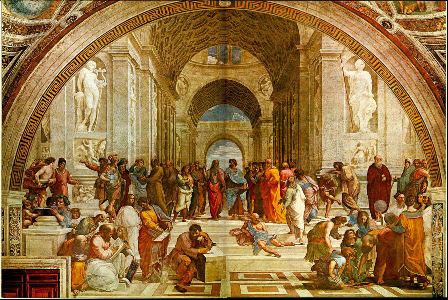

The figure of Socrates appears in the history of philosophy at the crossroads between sophists and phillosophers. We often recall Socrates for his contribution to ethics, politics, logic and epistemology and we consider his Apology as a foundation for morals. My purpose does not consist in trying to fret over the importance of Socrates, yet I must observe that, most of the time even academics fail to question wether there is something “more” to the figure of the philosopher. Most of the time we use the account of Plato – the dialogues – as the ultimate instrument in reconstructing, or better say imagining that figure and than we use it as a “given”. Even the fact that Plato was his disciple raises the question: Is this the real Socrates? What needs to be done – and I say it as a history student– is putting Socrates in the context of the ancient society of Athens, of the ancient ontological mode of being, and than we can hope that some explanation will unfold. Should we also try and take into account the other historical references –Xenophon and Diogenes – , well this would mean another step further. As the context and the historiogarphical approach are fairly bound to one another, I think these two are going to be the pillars of my analysis.

Born in 469 BC (suposingly his father was a stonemason and his mother a midwife), Socrates witnessed times of great political change; from the end of the Greco – Persian Wars to the Golden Age of Athens and the catastrophical defeat in the Peloponeasian war, the philosopher had his role in shaping the athenian society. As Plato tells, “he would spend his time amongst people, talking often so anyboday could hear him”. Aparently, Socrates dosen’t fall on the portrait of the tipical athenian. He used to talk right about everything with anybody, and unlike the sophists he wouldn’t charge his disciples. Questioning social and private behaviour, religious matters, education and political affairs in his original philosophical style, often than once his conclusions were afar from the “mainstream” ideas. Still – we’d say – he was living in a democracy; moreover, Athens was renouned for it’s libery of speech and expression. So the question raises: how was it possible that the very same society send Socrates to death in 399 BC with charges of impiety and corrupting the youth?

Well, the ancient man relates primarily to the city state, the poleis. But the individual framed to the poleis is bound to a natural order of respecting the gods, the laws and tradition. This order – that gouverns the life of the ancients – transcribes even in the athenian democracy: almost all magistratures were elected by draw. Not only this process would imply a spirit of justice and law, but it would also mean the divine decision on administrating the city. Furthermore, not only athenians but all greeks had an utmost respect for traditions, one of them being the sacred institution of family. Youth – up to an age – would be educated inside the family, only the rich having the posibility of hiring a teacher. In this paradigm, Socrates appear to question not only the fabric but the foundation of society and political practice: “But, say his accusers, <<Socrates makes those who converse with him contemners of the laws; calling it madness to leave to chance the election of our magistrates ; while no one would be willing to take a pilot, an architect, or even a teacher of music, on the same terms; though mistakes in such things would be far less fatal than errors in the administration.>> With these, and the like discourses, he brought (as was said) the youth by degrees to ridicule and contemn the established form of government ; and made them thereby the more headstrong and audacious.“ [1] This was an argument brought up in the trial of Socrates as mentioned by Xenophon in his Memorabilia, and I hope that looking through the glasses of the above explanation we can now understand the meaning of the accusation.

I also mentioned Socrate’s envolvment in the changes that took place in the Athens of his time. Altough he was not directly involved he had disciples who later became powerful rulers of the city as Alcibiades and Critias. As both of them are held rersponsable for a lot of dramatic events including treason, the defeat in the war, and attempts to overthrow democracy, people started having second thoughts about Socrates. The society – already enraged by the miseries of the Peloponesian War – started wondering wether he was actually harmless or his education led to the development of those two characters. Such arguments were brought in the trial. My purpose is not to make an apology for the philosopher, altough both Plato and Xenophon work so well on proving his innocence, but I insist on showing that the political context also had a great influence on the already controversial image of Socrates and played a key role to the death sentence delivered in 399 BC.

To return to our main objective, that of framing the life and death of the philosopher in a certain context, I think that by now we have a broader view on the matter, therefore can judge his image through different lenses. He was controversial for his time and he is controversial now because he was the first to die for his beliefs. As good as it gets, the romanian historian Zoe Petre notices that his death meant “the simbol of political intolerance twoards philosophical critique but also the remarcable importance of a creation (…) wich moves the debate about the essence of political universe, about human and gods, self, existence, and thought into agora.” Nontheless the historiographical approach is equally important, but it will be the subject of an article to follow.

[1] Xenophon’s Work, Philadelphia, Thomas Wardle Chestnut., p. 523